Feb 14, 2026

How Montel and MoFarm are pushing the boundaries of Vertical Farming

Habiba Bougherara and Lesley Campbell

Habiba Bougherara and Lesley Campbell

For over a decade, vertical farming has been hailed as a transformative force in agriculture, promising year-round production, local supply chains, pesticide-free crops, and efficient

land and water use. Early pioneers proved that leafy greens could thrive in controlled environments, attracting significant investment and global attention.

But recent years have revealed structural challenges. High capital costs, complex operations, and rising energy expenses have squeezed margins. Combined with a narrow crop focus on lettuce and herbs, many operators entered saturated premium markets with limited differentiation—leading to consolidation, bankruptcies, and a necessary industry reset.

Vertical farming works, but only under the right technical, economic, and crop conditions.

Why We Need New Innovations and New Crops

If vertical farming is to mature into a resilient and scalable food production model, it must evolve beyond its first-generation playbook.

First, crop diversification is essential. Relying heavily on leafy greens constrains revenue potential and limits market expansion. To unlock larger addressable markets, vertical farming must expand into higher-value, differentiated crops that command stronger price premiums and face less direct competition from conventional greenhouse or field production.

Second, new crop categories open new market channels. Retail salad mixes can only take the industry so far. Expanding into fruiting crops, nutraceutical-rich produce, specialty ingredients, and high-value berries allows vertical farms to engage foodservice, CPG brands, export markets, and even pharmaceutical-grade supply chains. Greater crop versatility strengthens economic resilience and reduces exposure to commodity pricing pressures.

Among the most promising frontiers in this shift are berries. Strawberries, raspberries, and other small fruits represent a multi-billion-dollar global market characterized by high spoilage rates, complex logistics, and strong year-round demand. They command premium pricing, have strong consumer loyalty, and benefit significantly from local production due to their perishability. Yet traditionally, indoor berry production has faced technical hurdles, particularly around pollination, yield consistency, and microclimate management.

The Pollination Barrier: Why Berries Are So Difficult Indoors

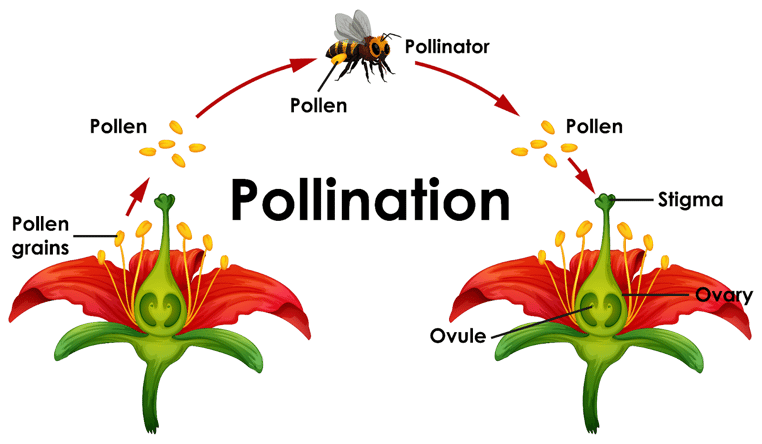

As vertical farming expands beyond leafy greens into fruiting crops like strawberries, it encounters a biological threshold: pollination. Unlike vegetative crops, berries depend on successful flower fertilization to produce uniform, marketable fruit. Poor pollination results in misshapen berries, inconsistent yields, and direct revenue loss. Indoors, this process becomes significantly more complex.

Image source: https://www.biopassionate.net/biologyimportanttopicsclass12/pollination-and-its-types

1. The Light Spectrum Mismatch

Most vertical farms use LED lighting optimized for plant photosynthesis, heavily relying on red and blue wavelengths. However, bees perceive light very differently. They are highly sensitive to ultraviolet (UV), blue, and green light, and nearly blind to red. Because most indoor systems lack UV wavelengths, the natural visual cues that guide bees to flowers disappear.

2. Disrupted Navigation

In nature, bees navigate using the sun and polarized light patterns in the sky. Vertical farms replace this with multiple artificial light sources, creating orientation conflicts. Without a clear directional reference, bees struggle to locate flowers and return to the hive efficiently, lowering overall pollination success.

3. Climate vs. Colony Needs

Indoor farms rely on strong airflow and tightly controlled humidity to prevent disease, especially in strawberries. However, turbulent air increases the energy cost of flight and can disrupt pheromone communication within the hive. The result is a technically optimized plant environment that is biologically stressful for pollinators.

Together, these factors make pollination one of the greatest barriers to scaling indoor berry production.

What If There Was One Primary Solution to Fix the Pollination Problem?

For years, the industry has tried to adapt outdoor pollination strategies to indoor environments, with limited success. But what if the answer was not managing bees better, nor replacing them with robots, but engineering the environment itself to perform the pollination?

That is exactly the question researchers at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) are tackling.

The TMU Innovation

Led by Professor Habiba Bougherara and Professor Lesley Campbell, the TMU research team is advancing a patented pollination system that uses airflow dynamics and precise microclimate control to autonomously transfer pollen between flowers.

Instead of relying on insects or manual vibration, the system applies controlled air movement patterns within the crop canopy. By manipulating airflow velocity, direction, and localized microclimate conditions, the technology stimulates pollen release and transfer in a way that mimics natural pollination.

In June 2025, the team was awarded up to $5 million in funding, supported by the Weston Family Foundation through the Homegrown Innovation Challenge. This investment signals strong confidence in the system’s potential to unlock scalable, pollinator-independent indoor berry production.

As Professor Bougherara notes, the goal is not incremental improvement, it is transformation. If successful, this approach could enable raspberries and other berries to be reliably grown in multi-layer indoor systems without biological pollinators.

A solution like this cannot remain theoretical. Airflow-based pollination requires an environment where ventilation, humidity, temperature gradients, and spatial layout are precisely engineered and measurable.

This is where MoFarm comes in.

Designed as a multi-level indoor microclimate farm, MoFarm provides a real-world testbed built on GreenRak™ multi-tier grow racks. It integrates intelligent air distribution systems with advanced environmental controls, all powered by digital electricity for precise performance monitoring.

MoFarm exists to answer a simple but critical question: Can this innovation work at operational scale?

The Engineering Backbone Behind Pollinator-Free Production: Montel

Advanced pollination systems require engineering excellence. Airflow, load distribution, rack design, ventilation architecture, and environmental control must function as one integrated system.

Montel brings decades of expertise in engineered storage and indoor vertical farming infrastructure. Their specialization in optimized multi-tier systems and controlled airflow environments makes them uniquely positioned to translate TMU’s scientific innovation into a scalable, repeatable growing model.

As Yves Bélanger, VP Sales – Indoor Vertical Farming at Montel, emphasizes, the mission is to help growers “grow more” within limited space, efficiently, reliably, and measurably.

By combining TMU’s scientific research with Montel’s engineering capabilities, MoFarm represents more than a pilot project. It represents a shift in how indoor berry production might finally overcome one of its greatest biological barriers.

A Turning Point for Vertical Farming

Vertical farming has reached an inflection point. The industry can no longer rely solely on leafy greens and first-generation systems if it aims to achieve long-term economic sustainability. High-value crops like berries represent both the opportunity and the challenge: they offer access to premium markets, stronger margins, and broader consumer demand.

Pollination has long been the invisible bottleneck in indoor fruit production. What TMU and Montel are building through MoFarm signals a new direction, one where environmental engineering replaces biological uncertainty, and where airflow, microclimate control, and infrastructure design become tools of reproductive precision.

If validated, this approach could redefine what is commercially viable in vertical farming.

And in that shift, berries may become more than a niche success story. They may become proof that the next chapter of vertical farming is not about growing more lettuce, it is about growing smarter, more versatile, and economically resilient crops at scale.

MoFarm is currently under construction. As the pilot farm evolves, Montel will share milestone updates through this page, including research progress, build phases, and key learnings.

If you would like more information, please don’t hesitate to contact Montel at 1-877-935-0236 and sales@montel.com

This article was produced in paid partnership with Montel. While Montel supported this piece, Agritecture maintains full editorial independence and is committed to creating content that is accurate, transparent, and genuinely useful to our audience. Disclosing our partnerships is a core part of our values and reflects our commitment to integrity and best practices in content creation.