Mar 17, 2023

One-of-a-kind 'agri-hood' would blend housing, farming and racial justice on Far East Side of Madison

Credit: Phil Brinkman for WSJ.

Editor’s Note: Projects such as this proposed “agri-hood” are reimagining the ways in which communities can provide access to housing and food security through frameworks of racial justice, collaborative leadership, and environmental sustainability.

CONTENT SOURCED FROM THE WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL

Written by: Dean Mosiman

March 17, 2023

In a first for Madison and maybe the country, an investor group wants to create a new neighborhood centered on low-cost housing, farming, racial justice and wealth building. It’s being proposed for an area of mostly wetlands and open agricultural land on the Far East Side.

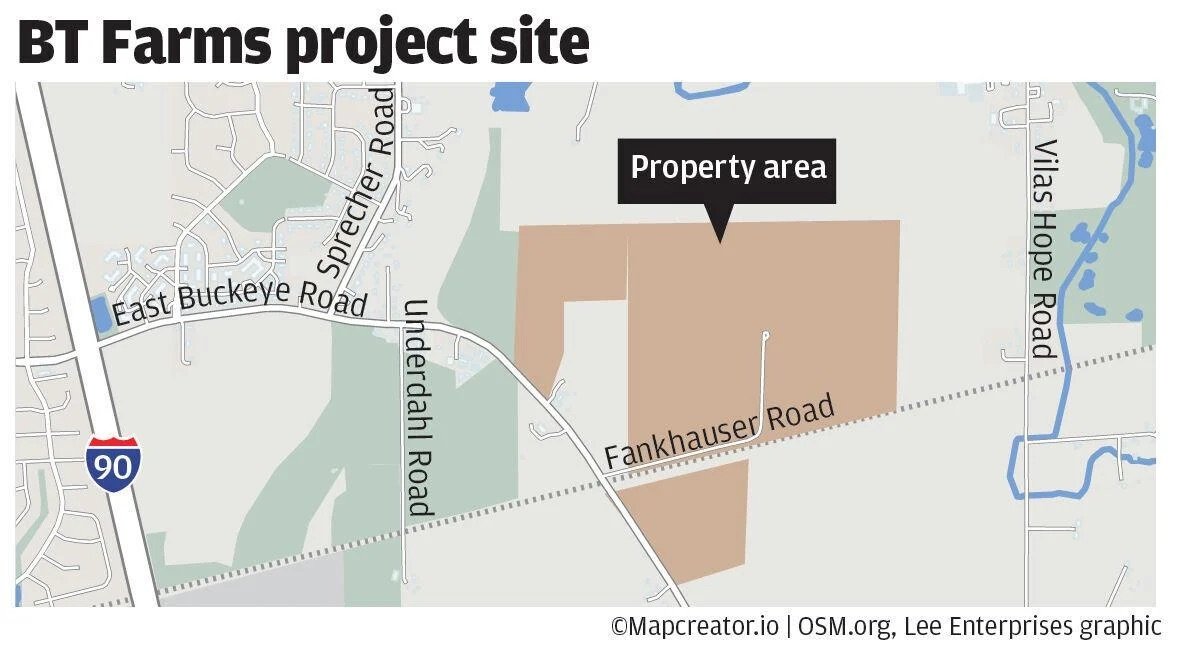

An anonymous group of investors, Bt Farms LLC, has engaged a team with local, national and international experience to help forward the “agri-hood” proposal, which will be shaped through input from the community and those who hope to live there. The group has already spent $4.9 million to buy three parcels totaling 222 acres off East Buckeye Road, east of Interstate 39-90.

“It is a low- to moderate-density project that works with and respects the land,” said Becky Steinhoff, the former longtime executive director of Goodman Community Center on the East Side tapped by the investors to help facilitate the project. “It will preserve farmland and grow food to feed people. It will restore 70 acres of wetlands and create hiking and skiing trails for residents.”

“The project will promote home ownership and wealth generation for low-income residents,” she said. “It will be cooperative and governed by residents. It will be a green development. We have not yet found a model like it.”

Credit: Wisconsin State Journal.

The project’s planners, Bt Farms Foundation, is a diverse team led by Black women with expertise in design, landscape architecture and urban planning, urban agriculture, ecology, geography, real estate, finance and engineering.

“The Black and Indigenous communities of Wisconsin have had a legacy of farming for nearly 3,000 years,” said Ifeoma Edo, Bt Farms project planner. “Historic African American settlements such as Pleasant Ridge and Cheyenne Valley — as a historic, Black-led community of farmers and places of refuge and empowerment — is a part of that legacy, prematurely halted due to racist violence.”

In the 1800s, Black settlers founded farming communities at Pleasant Ridge near Lancaster and Cheyenne Valley near Hillsboro and fostered such achievements as the distinctly traditional round barn and, possibly, the first integrated school in the nation, accounts show.

“These historic communities of color embody an approach to community development that we hope to emulate,” she said.

City Council Vice President Jael Currie, 16th District, who represents the site, said she’s intrigued and excited about the possibilities but hasn’t been briefed on the details and has requested a meeting with the project staff.

A legacy project

Steinhoff said the investor group that bought the property wanted to create an “agri-community” and contacted her about facilitating the project in early 2021.

By happenstance, Steinhoff had attended a Downton Madison Inc. annual event that year and the keynote speaker was Ebo, founding principal of Creative Urban Alchemy, a design and planning consultancy based in New York. They met and continued communicating about working together and entered a formal contract in the fall of 2022, with Ebo bringing her team to the project and Steinhoff recruiting the local members.

The anonymous investors are local and national, Steinhoff said. They are not looking to turn a profit, she said.

“This is a legacy project for them,” she said. “They believe that Madison will embrace such a project and that many, including our city and county leaders, will get what we are doing and understand the significance and impact could be.”

“Madison needs affordable housing stock. It needs strong, vibrant, high-quality developments that support our BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) residents,” she said. “Madison needs a development that is innovative and outside of the box of traditional development models. There is also a desire to include the Ho-Chunk, as this was Ho-Chunk land.”

The investors do have a small number of “must haves,” Steinhoff said, but are leaving the details to the project team and community. According to Steinhoff, the project must:

Be community organized around a working farm;

Include low-cost housing;

Be shaped by people who might want to live there and designed by a diverse group of professionals;

Respect the land and restore or preserve the natural features including a drumlin and wetlands;

Be sustainable and as close to energy independent as possible; and

Have community amenities to support residents and avenues to create businesses and jobs for them.

“There are many agri-hoods being developed across the country, but most are high-end housing with minimal interaction with the farming,” Steinhoff said. “Residents do not farm the land or own or work in the businesses within the development.

“Cooperative urban farming means that all residents work together and contribute to the agriculture and other spin-off businesses’ success,” she said. “This could be just a few hours a week around another full-time job, or it could be full-time work on the property. Our project scope is very unique.”

“The uniqueness of this project is its centering of marginalized communities,” Ebo said. “With that said, we are inspired by Soul Fire Farm in Petersburg, New York, or Sweet Water Foundation in Chicago. Both are agri-communities that center Afro-indigenous communities and themes of regeneration, liberation and reparations in their formation and governance.”

Bt Farms’ scope is bigger and deeper, Steinhoff said.

“We have a lot to figure out in the governance structure, but we are hoping to develop a structure where the cost of living in the community is tiered, based on how much you are able to contribute,” she said. “Everyone does not have to be a farmer either. There will be lots of ways to work within the community.”

“While anyone can live in the community, we are looking to create safe and welcoming spaces, housing and businesses for the BIPOC community,” she said.

Building wealth

Currently, the site holds about 70 acres of wetlands that are in poor shape, with three spring-fed ponds, a drumlin, stands of trees, a private dog park, a farmhouse with barn and silos, and 115 acres of open space that’s been used as agricultural fields. Bt Farms is now in the process of planting alfalfa as a cover crop so the land can heal and be converted to organic soil, Steinhoff said.

The concept for the site includes houses, small apartment buildings, farmland, an educational facility, a community center, greenhouses, natural areas with walking trails and perhaps boardwalks through some of the wetlands, playgrounds and play space, commercial space and maybe a wellness center/business incubator.

“We have not seen this type of development in the city of Madison,” city urban planner Jeff Greger said. “There are portions of their plan (like farming activities) that could be implemented today given the zoning of the property and what is outlined in the Yahara Hills Neighborhood Development Plan. Other parts of their plan, like the housing, will require rezoning and other approvals.”

The intent is to avoid a high-density housing development, but the number of units, breakdown between single- and multifamily, and mix of low-cost and market-rate housing is undetermined, Steinhoff said. “The desire is for the majority of the housing to be for low-income to working class,” she said.

“From homeownership, to viable businesses that are owned and/or employ residents, the project will strive to build generational wealth for residents,” she said. “Part of the planning process is business feasibility studies and planning based on the input we get from the community.”

The exact type of farming is unclear and will emerge from the community planning process, with the project hiring a farmer who will work with the residents to farm,” she said.

Credit: John Hart for WSJ.

The Bt Farms team includes Shellie Meier, who has extensive experience as an agriculture developer and helped create Badger Rock Middle School in Madison, the state’s first charter school centered around agriculture, biodiversity and environmental studies. Her father still runs a farm and the South Madison Farmers’ Market.

“This project is striving to provide opportunities for members of the diverse BIPOC communities, who are interested, to be a part of the growth and development of this community as a form of restorative justice,” Ebo said. “We hope that this community development will encourage new legacy building, including the building of wealth in families and communities through farming and building of new enterprises.”

“We are currently reaching out to nonprofit organizations who are and have been working in and with BIPOC communities supporting initiatives that center around food sovereignty, environmental justice, community gardening and farming, health and wellness, community education and workforce development,” she said. “We want to partner with them in both creating and implementing a unified vision for this land and this community and the future stewardship of the natural resources.”

“So far, I think Bt’s vision has been received well by staff, but it is still very early in the process and there are challenges to be sorted out,” Greger said. “Connecting the property to city utilities will be challenging. Also providing adequate access to the site will be a challenge.”

The potential cost of the project is unknown and would be funded by a mix of investors, grants, home sales, private contributions and tax credits, Steinhoff said.

After initial community outreach, the Bt Farms team will produce more finished concepts for community review, cost estimates, proceed to secure an architect and developer for the project and submit formal land use plans to the city, she said, adding, “it will be a few years before we get a shovel in the ground.

“In the end,” she said, “Bt Farms will not run anything. There’s no desire to own anything. The community and partners will run and own it.”