Mar 23, 2022

Regenerative Agriculture Needs A Reckoning

Editor’s Note: In calling for an urgent change in farming practices, “regenerative agriculture” has become a major buzzword in many agriculture and climate circles. While we know that the practice could sequester between 14.52–22.27 gigatons of CO2 between 2020 and 2050 (according to Project Drawdown estimates), the industry is yet to agree upon one definition for “regenerative agriculture.” As an industry, we need to come together to have uncomfortable conversations about equity access, and agree upon such definitions to ensure that we can tread forward. Here’s an article about a biologically diverse farmstead that is successfully using regenerative practices to bring fresh produce to their community.

Why avoiding uncomfortable conversations about equity, race, and access threatens to spoil a nascent movement’s environmental promise.

It hardly matters if you’re dealing with food justice activists or tech-startup entrepreneurs. Small, independent farmers or the corporate leadership of agribusiness giants. Policy wonks or research scientists. Everyone is talking about regenerative agriculture. Some even say it’s the future—and not just of farming. The most fervent advocates say so-called “regenerative” practices have the power to restore the balance between human beings and nature, a solution finally big enough to save our beleaguered planet from all of us.

Buoyed by the optimism of food producers, foundations, and corporate leaders, the term has gained new levels of visibility in the past two years. It’s spawned books by farmers and filmmakers, features in The New York Times and The Washington Post, and at least one full-length film—Kiss the Ground, a Netflix-distributed documentary. It’s become a marketing buzzword in the corporate world, too, with companies like McDonald’s, Target, Cargill, Danone, General Mills, and others pledging to use funds to support regenerative practices. The term has even been applied as a modifier to individual food products: In 2019, Applegate Farms, a subsidiary of major meatpacker Hormel Foods, debuted a line of “regenerative” sausages.

That private-sector momentum may soon get a public-sector boost. Advisers to President Joe Biden have suggested that the new administration launch a carbon bank for farmers as part of a plan to fight climate change, using the Commodity Credit Corporation—the same government war chest President Trump used to bail out mostly white, mostly wealthy farmers for income lost due to his trade war—to pay agricultural producers to sequester carbon in the soil.

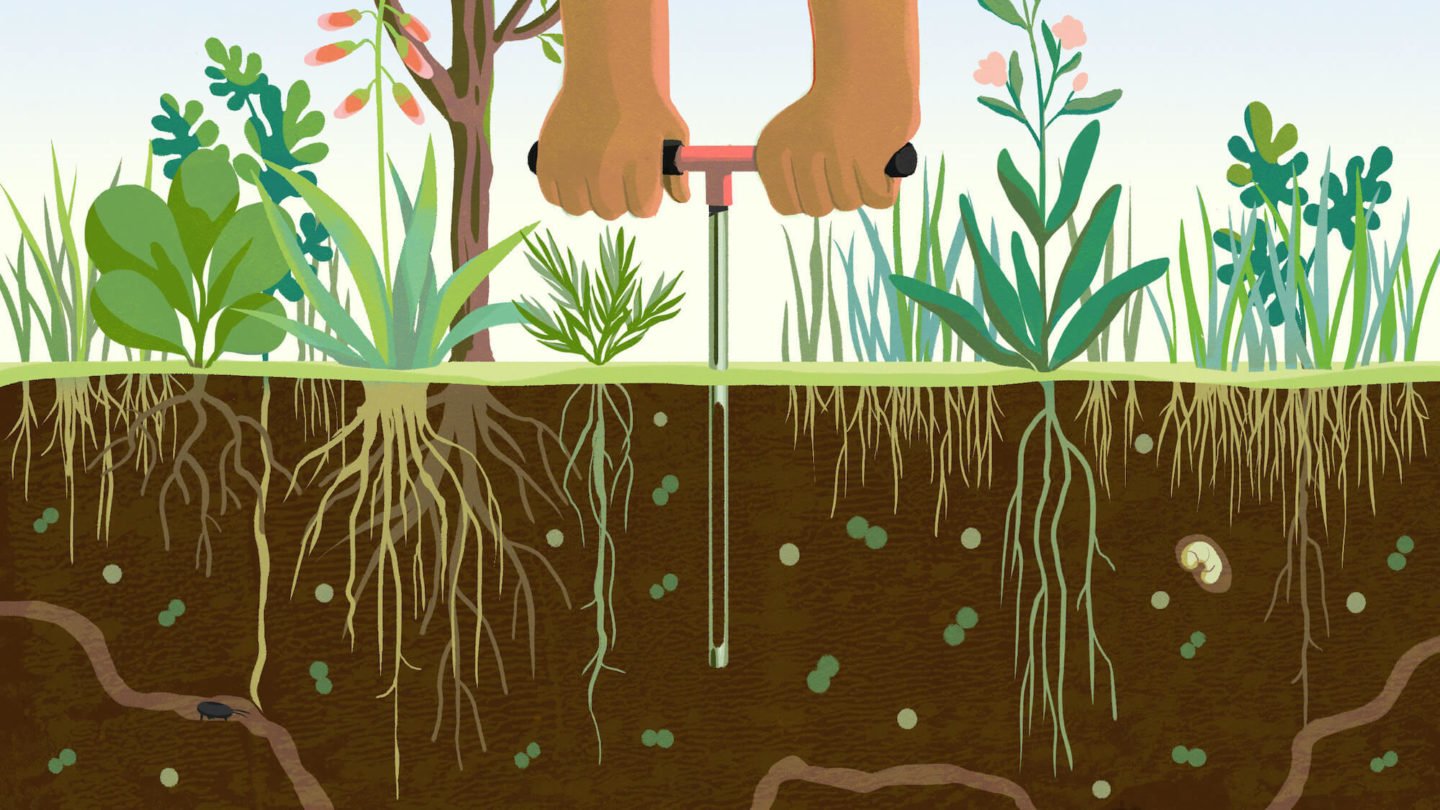

Image credit: Cornelia Li

It’s a promising idea. Advocates for regenerative farming argue that agricultural fields can help bury carbon deep under the ground, offsetting the disastrous climate effects of burning fossil fuels—and that potential promise is a central part of its appeal. Even members of the U.S. Senate, not lately known for their consensus-building abilities, have crossed party lines to get on board.

But the growing, still-incipient movement harbors a secret below its hopeful surface: No one really agrees on what “regenerative agriculture” means, or what it should accomplish, let alone how those benefits should be quantified. Significant disagreements remain—not only about practices like cover crops, or the feasibility of widespread carbon capture, but about market power and racial equity and land ownership. Even as “regenerative” gets increasingly hyped as a transformative solution, the fundamentals are still being negotiated.

A growing movement harbors a secret: No one really agrees on what “regenerative agriculture” should mean.

That lack of consensus is visible at the most basic level. In a new study published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, scholars from the University of Colorado, Boulder looked at how regenerative agriculture was defined across 229 academic journal articles and 25 practitioner websites. They found that only 51 percent of research articles that used the term supplied any sort of definition, while 84 percent of practitioner organizations did. Meanwhile, among the sources that did provide a definition, the details varied dramatically.

Many—but far from all—of the sources surveyed said that “regenerative” was about improving soil health, or sequestering carbon. For some, the term meant using no-till practices or planting cover crops. For others, it was about integrating livestock and crop production, or improving animal welfare practices. For still others, it was about improving human health, or food access, or food safety. Some said it was about supporting small-scale systems. Others said it was about improving the social and economic well-being of communities, regardless of farm size. Some said it was about increasing yields. Some said it was about increasing profit.